Irony & Theme

I believe that most screenwriters (as well as wannabe screenwriters) are thinking about the wrong issues when writing these days. If your mind is swirling with surprising plot twists, clever story revelations, or, God forbid, what you assume the audience wants to see, then you’re thinking about the wrong things.

I say this with authority having spent many years of my life thinking about surprising plot twists, clever story revelations, and what I assumed the audience wanted to see. What you ultimately end up with are stories that are highly similar to other stories you’ve already seen or heard. What you ought to be thinking about is motivation — why are these characters doing the things they’re doing? This is where things get interesting. Human beings don’t necessarily do things for good or rational reasons, but, nevertheless, there are always reasons. There is a chain of logic, even if the events themselves are entirely illogical, that has caused us to do all the things that we have done. People don’t just act for no reason, unless they happen to be characters in a bad movie.

The motivations for almost everything we human beings do is not based on altruism or good intentions but on the concept that we are our own worst enemies. Given a choice of doing what’s best or what’s worst for ourselves, we will frequently choose the worst. Why? Because, whether we realize it or not, human beings are ironic characters, and we deeply love the idea of irony. So, what is irony exactly? Webster’s New Twentieth Century Unabridged Dictionary defines it as “a combination of circumstances or a result that is opposite of what might be expected or considered appropriate.” The really surprising twists and revelations in stories do not come from the plot; they come from the characters’ ironic motivations.

Take my life as an example, since it’s loaded with irony. I have dedicated my entire life to feature filmmaking — I have studied it, obsessed about it, and care about very little else in life — so what am I doing now? I’m working in television. My hobby is my passion, and my career is an afterthought. That’s ironic. But also not unusual.

I know a guy who was a top chef at several fancy restaurants here in L. A. Although he was never much of a smoker, he developed cancer of the tongue and had to have a quarter-sized hunk removed, which included his taste buds. Now he can’t taste anything and he can no longer be a top chef. If we don’t care to be ironic, God or fate will do it for us.

Just like with irony, a writer ought to be considering the story’s theme constantly. Used properly, the theme ought to be touched on in every single scene if possible, but certainly every scene the lead character appears in. In fact, every line of dialog the lead character speaks ought to refer to the theme in some way.

Writer-director Frank Tashlin said that he always boiled the theme down to one word, which is a good way to go. In his film Will Success Spoil Rock Hunter? the word was success, and every single scene is about success in one way or another. Sadly, the theme of most films is generally not found in the title. A really good theme not only covers the actions of the lead character, but those of as many other characters as possible, too. This is hard to do. In the twenty-eight scripts that I’ve written, I haven’t yet found a theme that strong.

A theme is much easier to recognize in a song than in a script or a story — mainly because songs are short, and often, the theme appears in the song’s title — and it’s used exactly the same way as a screenplay.

In Pink Floyd’s song “Time,” lyricist Roger Waters does a brilliant job of sticking to his theme:

Ticking away the moments that make up a dull day

You fritter and waste the hours in an off hand way

Kicking around on a piece of ground in your home town

Waiting for someone or something to show you the wayTired of lying in the sunshine staying home to watch the rain

You are young and life is long and there is time to kill today

And then one day you find ten years have got behind you

No one told you when to run, you missed the starting gun

Marvin Gaye’s wonderful song “Too Busy Thinking About My Baby” (written by Norman Whitfield, Janie Bradford and Barrett Strong). I’d say the theme is being “busy.” Now we’re going to get a list of all the possible things he could be doing were he not so busy thinking about his baby.

I ain’t got time to think about money

Or what it can buy

And I ain’t got time to sit down and wonder

What makes the birds flyI ain’t got time to discuss the weather

Or how long it’s gonna last

I ain’t got time to do no studying

Once I get out of classI’m too busy thinking about my baby

I ain’t got time for nothin’ else

Being so brief, a song’s theme and its subject are generally the same thing. In a screenplay, with over one hundred pages to deal with, the theme comes out of the subject but is generally not the same thing. Being busy is not a suitable theme for a story, although it’s a fine subject.

Here is my best attempt at thematic song writing to date. This is the first verse of the rap song called “The Nervous Meltdown,” which I wrote for my film Lunatics: A Love Story (music by Joseph LoDuca):

The core in your brain is cherry red

There’s a crack in the reactor inside your head

When your fission and fusion do the wild thing instead

Yo man, you’re having a nervous meltdown.

You state the theme in the title and then you try to pursue it in every line of the song. It ought to be that clear in a story, too.

I just read the first thirty pages of a script by a guy who claimed to know all the rules of screenwriting, and was insulted when I suggested that he read my essays about story structure. “That’s Screenwriting 101,” he sneered. But thirty pages into his script he not yet stated a theme nor even established a lead character. I said, “You may know all the rules of screenwriting, but you’re not following any of them.” He replied, “I’m a rebel.”

He’s not a rebel; he’s just a bad writer. On an important level, the difference between a good writer and a bad writer is that the good writer is at least trying to follow the rules, while the bad writer either doesn’t follow them or feels that they are above them.

I read another troubled script recently. At the end of twenty-five to thirty pages, I found no theme, no character with any kind of need or desire, no drama, just scene after scene of meaningless talk. I tossed the script in the shitter and wrote a fairly long email to the screenwriter explaining why I didn’t like it. In both of these instances I was confronted with, “But you only read the first 30 pages! How can you possibly know what you’re talking about?”

Just how broken does something have to be before you decide that it’s broken? If I drop a light bulb on the floor and it shatters, must I inspect every little jagged piece of glass before concluding that it’s broken? Furthermore, it makes absolutely no difference if either of these scripts turned into Hamlet on page thirty-one because the first thirty pages would not support what follows. If there’s no foundation, it doesn’t matter how pretty the walls and the roof are; they will collapse.

I run into the same Goddamn problem with every single screenwriter wannabe that I encounter — they won’t be hemmed in by any of the rules — they’re all rebels.

You do not have to be a rocket scientist to figure out how to write a decent script. But you do have to be willing to put in some plain old hard work. A script isn’t going to come out the ends of your fingers properly structured with a functioning theme and fully formed characters — it ain’t gonna happen. If you don’t put in the time confronting each of these issues and working them out, your script will won’t be any good, just like the other eight million other shitty scripts floating around Hollywood. In fact, there are enough bad scripts here to build another, bigger, Hoover Dam.

Perhaps it’s the word rules that makes people so uneasy. I was as rebellious and antiauthority as any young person, but when I decided that I wanted to be a screenwriter, I came to accept the disciplines of the craft. These are concepts that you simply must know to do the job well.

Writing is a discipline, like weightlifting. The structural and thematic rules are the weights. You can certainly proclaim, “I’m a rebel, and I won’t lift those weights,” but then you’re not a weightlifter; you’re a blob standing around the gym getting in other people’s way.

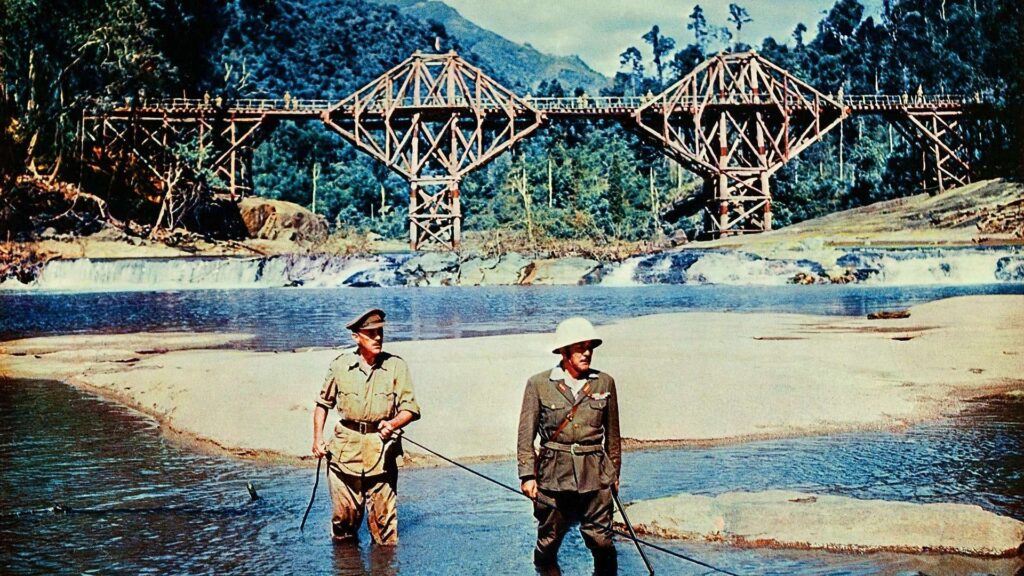

As I see it, no one has yet written a better script than The Bridge on the River Kwai. Yes, it’s based on a good book, but the script is actually better than the book, and that’s certainly a rare occurrence. Since screenwriters Michael Wilson and Carl Foreman were both blacklisted due to the communist witch-hunts of the 1950s, neither writer got screen credit until the film was restored in 1997, sadly after both of them had died. What makes this script so special? That it’s a World War 2 POW camp story? I don’t think so; there are plenty of those. That the prisoners build a bridge? Or perhaps that commandos blow it up? I’d say it’s none of those things. That’s all plot stuff, and it’s important, but it’s not what makes the script so good.

Irony and theme are what make it so captivating — plus, it’s beautifully directed, shot, and cast. The story’s basic great irony appears on page 1 of Pierre Boulle’s book — a Colonel in the military is the same person in any country in the world: an uptight, unbending, humorless prig, with an extremely overdeveloped sense of duty.

You may have watched this film a hundred times and never noticed that and it doesn’t matter in the slightest because it’s there. The main irony as well as the theme (which is about duty) and the main dramatic conflict are all occur the first ten minutes of the film. You just can’t do any better than that. Most films these days do not have these issues figured out over the entire course of two or more hours.

So, let’s say that Boulle began conceiving this story with his ironic observation that colonels are the same the world over (it is on page 1). Okay, maybe that’s true, but it’s not a story. For it to be a story you must have a dramatic conflict. To make the point what you need are two colonels from different countries confronting each other. How about a battle? Well, two colonels will never realistically end up face to face in a battle; if they did, they’d just kill each other. How and where do you get them to face off and have a chance to speak? How about in a prison camp in the middle of the jungle, where one of the colonels is God and the other colonel is a prisoner? And, since World War 2 had ended just a few years earlier (the book was copyright in 1952) and was still on people’s minds, why not situate the story during the war? Thus, we have a setting, a subject, and a theme, and we haven’t mentioned bridges, escape attempts, espionage teams, or anything else about the plot.

What The Bridge on the River Kwai is about — and you absolutely can’t believe you’ve gotten there in the first ten minutes — is Colonel Saito smacking Colonel Nicholson across the face with the Geneva Convention rulebook. The two lead characters have reached the main dramatic conflict of the story and the front titles just ended! We’re stuck in the middle of the jungle — where can this possibly be going? That’s exactly what you want the audience to be wondering at the beginning of your story and also what makes the narrative so breathtaking.

Because it’s so sweetly ironic that these two colonels should ever possibly end up face to face in a dispute over the meaning of duty, that which the original author felt he had to point out on page one of his book, the screenwriters don’t illustrate until over thirty minutes into the film, and when they do they get a big laugh. It occurs when each colonel independently proclaims the other Colonel to be “mad.” The screenwriters don’t tell us the Colonels are the same, we observe it ourselves. But that’s not the only irony inherent in this situation; there is yet another, bigger irony looming. The prisoner, Colonel Nicholson, wins the dispute with his captor, Colonel Saito, who is actually in a worse situation than Colonel Nicholson; if he doesn’t get that bridge built on time so that the troop train can come across it on the specified day, he will have to kill himself. He informs Colonel Nicholson of this and asks, “What would you do?” Nicholson shrugs, “I suppose I’d have to kill myself.”

The Bridge on the River Kwai is not great because it has soldiers and machine guns and explosions or even because it’s beautifully directed and photographed; it’s a masterpiece because it’s got such a terrific sense of irony and an incredibly strong and true theme, and the situation is the perfect one to exploit these things.

That Wilson and Foreman are then able to take the theme of duty and weave it back through every other major character — James Donald, the doctor; William Holden, the apathetic prisoner; Jack Hawkins, the lead commando; and Geoffrey Horn, the young saboteur — and tie up every one of them at the end is brilliant and utterly breathtaking. That a bridge blows up (in real time, no slo-mo) is icing on the cake.

That Wilson and Foreman are then able to take the theme of duty and weave it back through every other major character — James Donald, the doctor; William Holden, the apathetic prisoner; Jack Hawkins, the lead commando; and Geoffrey Horn, the young saboteur — and tie up every one of them at the end is brilliant and utterly breathtaking. That a bridge blows up (in real time, no slo-mo) is icing on the cake.

The Bridge on the River Kwai has been more important to me as a struggling screenwriter than any book I’ve ever read on the subject, and several books have been quite important to me. But everything you need to know about screenwriting is right there, gorgeously photographed on location in what was then called Ceylon.

If irony and theme are not subjects that you want to think about constantly for the rest of your life — dream about, muse about, give yourself headaches about — you might consider pursuing another profession besides screenwriting.